REFLECTIONS ON MY DELEGATION TO PALESTINE/ISREAL WITH INTERFAITH PEACE BUILDERS

Background on Interfaith Peace Builders: “Interfaith Peace-Builders fosters a network of informed and active individuals who understand the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the United States’ political, military, and economic role in it. To build and nurture such a network, we lead delegations of people from diverse backgrounds to Israel/Palestine. These delegations emphasize listening to and learning from those immersed in the reality of the conflict, and advancing the work of Israelis and Palestinians committed to nonviolent struggle and peace with justice.” Visit http://www.ifpb.org/about/default.html for more information.

Reflection 1: Beyond Displacement – May 18, 2017

As our delegation traveled around East Jerusalem yesterday, my heart repeatedly sank with grief. My heart sank with grief as we learned about Israel’s persistent efforts to expel the Palestinian population of East Jerusalem from their homes and neighborhoods, in an attempt to create more space for Jewish-only settlements well beyond the internationally recognized Green Line (that is meant to separate Israel from the Occupied Palestinian Territories).

We learned that to drive Palestinian residents out of their homes and communities, the Israeli government employs a meticulous program of outright house demolitions, the denial of building permits to Palestinian residents (94% of Palestinian applications for building permits in East Jerusalem are rejected), and the positioning of the so-called “separation wall” in such a way as to bisect Palestinians communities, making movement so arduous, costly, and time-consuming that Palestinians will self-select to relocate.

We learned that Israel uses intimidation and criminalization of non-violent protest to chill Palestinians who attempt to speak out against these and other abuses into silence (sometimes successfully, sometimes unsuccessfully). We learned that Israeli media outlets misrepresent or simply do not cover Palestinian resistance efforts, ensuring that most of the Israeli population will remain pitted against them.

As we traveled around East Jerusalem yesterday, I felt my heart sinking with grief for the Palestinian residents and former residents of this land, who endure and have endured so much injustice for so long. However, I realized that the grief I felt stemmed also from my recognition that the horrifying reality I saw around me was, in so many ways, not so different from the conditions that exist right now in predominantly Black and Brown communities across America.

Boston Massachusetts, my hometown, is one of the most racially segregated cities in the United States. My father, who lived in Boston himself back in the 1980s, told me that a Bostonian real estate agent once asked him directly and without remorse “do you want me to show your property to Black people.” I do not know to what extent such blatant and unapologetic racism continues to exist today, in conversations conducted between Bostonian home buyers, sellers, leasers, and renters behind closed doors.

I do know that the Boston Planning and Development Agency (BPDA) recently passed a rezoning plan called “Plan JP/ROX” over the expressed wishes of the mostly Black and Brown community members who will be most impacted by the plan. Plan JP/ROX will increase the amount of land available for new residential developments in neighborhoods presently sought out by predominantly white and predominantly middle/upper class newcomers who are hungry for high-end housing in what has become a red hot market. Plan JP/ROX’s weak affordability requirements for new developments ensure that an enormous proportion of current Black and Brown residents, who have lived in these neighborhoods for decades and who have put their hearts and souls into building strong and mutually supportive communities in the face of persistent public neglect, will soon be priced out and forced to start anew somewhere else.

The actions Israel uses to displace Palestinians from their homes and land may be more direct and more extreme than those America uses to displace Black and Brown people from their communities. (It should be emphasized that Israel’s actions are by no means more extreme than those America has used and continues to use to dispossess our own continent’s indigenous nations from their land.) It strikes me, however, that the intention and the impact undergirding these action are largely the same in Israel and in America: One group of people want land, so they do everything they can to drive away those who live on the land now.

And the parallels between the United States and Israel go beyond displacement. From the intense patriotism conveyed by countless Israeli flags staked into nearly every building and landmark imaginable, to the outspoken contempt Israeli passersby expressed for our Palestinian tour guide. From the pervasive and ostentatious militarism on display by the Israeli Defense Force soldiers positioned at every entrance and major intersection of Old City, to the towering wall (positioned East of the internationally recognized Green Line) that separates Palestinians from their families, friends, and places of work.

In all of these respects, what I saw in East Jerusalem yesterday struck me not because I had never seen anything like it before, but because I began to recognize that I had seen it my whole life. The flags, the disdain for difference, the militarism, the walls and fences and borders meant to limit movement. Perhaps I needed to travel across two oceans to truly appreciate the state of my homeland. What I witnessed yesterday in East Jerusalem served as a grotesque hyperbole of my own country, a concaved reflection of what America is today, and a warning of what America could more fully become in the not-so distant future.

And throughout our tour of East Jerusalem, I held in my mind that these similarities are not incidental. We, the American people, fund the Israeli military through our tax dollars. We send our police commissioners to Israel to learn how to carry out upon Americans the violence that the Israeli military has honed and refined through decades of everyday operations on Palestinian land. And I held in my mind that effective resistance is urgently important, even when the personal cost is high, because justice and survival are never guaranteed.

Reflection 2: With Steadfastness – May 25, 2017

We will return. That is not a threat, a wish, a hope, or a dream, but a promise. –Remi Kanazi

Over the course of our travels this past week, members of our delegation repeatedly questioned whether or not true change bringing justice to the Palestinian people is possible to achieve. Israel, after all, boasts one of the world’s most powerful and well-funded political lobbies, not to mention their support on the international scene from (as Noam Chomsky once put it) the biggest thug on the geopolitical block, the U.S.A. Is there anything Palestinians and international advocates can do to bring an end to Israel’s ongoing colonization of the West Bank, to abolish Israel’s apartheid legal and criminal justice systems, and to compel Israel to respect Palestinian human rights?

I noticed, however, that the Palestinian people we have had the opportunity to meet over the course of our delegation so far have not paused to raise such questions. For them, the struggle for justice, it appears, is one undertaken not as the result of a measured calculation of the likelihood of success but out of sheer necessity. Cynicism and doubt, it seems, are simply not a luxury they can afford.

As one example, when we had the opportunity to speak with prominent Palestinian human rights defender Issa Amro, one delegate asked Issa, “What can people in the U.S. do to support your struggle?” Issa responded, “Get your representatives speak to out on Israel’s abuses of Palestinian human rights.” When I quietly mumbled, “that would be nice,” Issa promptly turned to me and exclaimed: “No. You have to work at it.”

Issa is not naïve. He knows as well as I do how challenging it is to get Palestinian human rights on the political agenda in the United States. But Issa cannot afford to resign to the belief that such challenges are insurmountable. Issa insists upon the efficacy of this struggle, regardless of what stands in the way, because his community and his homeland hang in the balance. And he expects nothing less from internationals like me.

Issa’s resolve is not exceptional among Palestinians. From the 1,700 Palestinians prisoners on hunger strike for the basic rights Israel’s military court and prison systems deny them (for 38 days and counting at the time of this writing); To the Palestinian refugees living in the Dheisheh camp who have continued to believe, for 69 years, that they will return to the villages from which Israel forcibly expelled them in 1948; To the residents of occupied Hebron, who refuse to leave the city even in the face of daily harassment and violence from Israeli settlers and soldiers that is meant to make their lives so miserable that they abandon their homes.

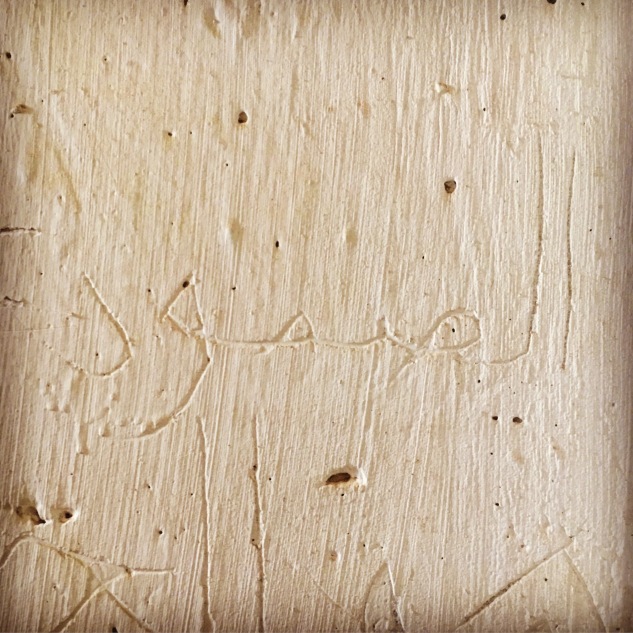

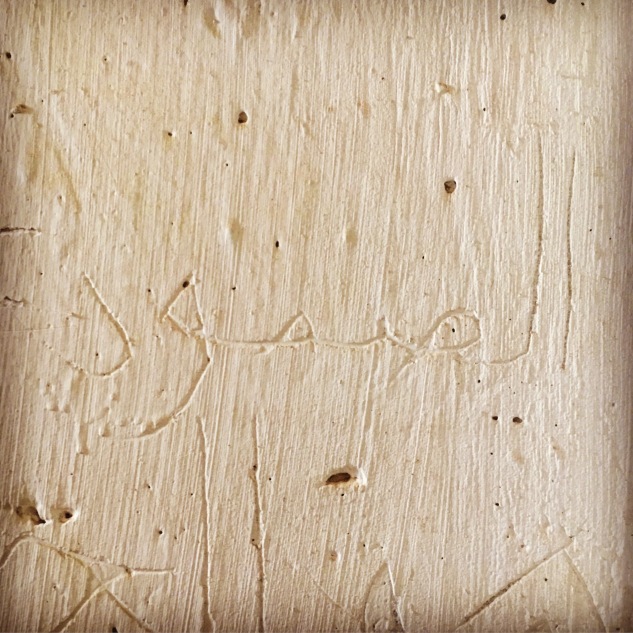

The attitude and ethos of the Palestinian people is perhaps best encapsulated by the Arabic word sumud. In English, sumud means steadfastness. The Palestinian people we met over the past week embody sumud in their persistent refusal to give up and back down in the face of Israel’s constant efforts to break their bodies and their spirits.

Israel and their allies abroad may outmatch the Palestinian people and those who struggle with them when it comes to lobbying power. Israel and their allies abroad may have the funding and resources to send countless internationals on free propaganda trips that promote a false and malicious narrative about Palestine/Israel.

But the Palestinian people have the sumud to continue fighting. And bearing witness to this sumud, internationals like me will continue to find new resolve to more fully commit to the task winning support for the struggle for justice in Palestine in our respective communities. When I find myself doubting the efficacy of this struggle or fearing that change is impossible, I will remember Issa’s prompt and unflinching response to my expression of doubt two days ago: We have to do the work, with steadfastness, because too much is at stake.

Our delegation visited a former Israeli prison in the West Bank, in which Palestinian prisoners were once packed with as many as 15 other prisoners into cells with dimensions of about 10×4 feet. One prisoner carved the word sumud (in Arabic above) into their cell wall. Photo Credit: Steve Pavey, IFPB Delegate

Our delegation visited a former Israeli prison in the West Bank, in which Palestinian prisoners were once packed with as many as 15 other prisoners into cells with dimensions of about 10×4 feet. One prisoner carved the word sumud (in Arabic above) into their cell wall. Photo Credit: Steve Pavey, IFPB Delegate

Our delegation visited a former Israeli prison in the West Bank, in which Palestinian prisoners were once packed with as many as 15 other prisoners into cells with dimensions of about 10×4 feet. One prisoner carved the word sumud (in Arabic above) into their cell wall. Photo Credit: Steve Pavey, IFPB Delegate

Our delegation visited a former Israeli prison in the West Bank, in which Palestinian prisoners were once packed with as many as 15 other prisoners into cells with dimensions of about 10×4 feet. One prisoner carved the word sumud (in Arabic above) into their cell wall. Photo Credit: Steve Pavey, IFPB Delegate